Page Content

FINAL REPORT – Over the course of three years, the FINAL project saw five Alberta high schools and seven Finnish high schools take part in a partnership that involved leadership summits, student exchanges and numerous student projects.

When I joined the Finland-Alberta (FINAL) partnership in 2010, I was convinced that this new work was going to be something beneficial depending on, of course, how much I was willing to learn from other people and, conversely, invite them to benefit from my expertise. As I look back to the launch of the partnership at the Educational Futures symposium in November, 2010, sponsored by the Alberta Teachers’ Association and the Finnish Ministry of Education, the people in the project were motivated, highly professional, willing to work for their goals and had similar educational backgrounds. Despite our linguistic differences (Finnish and English), as teachers we all spoke the same language: we wanted to focus on the development of students as whole persons.

When I joined the Finland-Alberta (FINAL) partnership in 2010, I was convinced that this new work was going to be something beneficial depending on, of course, how much I was willing to learn from other people and, conversely, invite them to benefit from my expertise. As I look back to the launch of the partnership at the Educational Futures symposium in November, 2010, sponsored by the Alberta Teachers’ Association and the Finnish Ministry of Education, the people in the project were motivated, highly professional, willing to work for their goals and had similar educational backgrounds. Despite our linguistic differences (Finnish and English), as teachers we all spoke the same language: we wanted to focus on the development of students as whole persons.

The FINAL project was not like anything I had ever participated in previously since we naïvely (some might say) hoped to create ideal circumstances and be given the freedom to invent school-based projects to find ways of co-operating under the ambitious umbrella question of “What makes a good school for all?” Fortunately for we Finns, the Finnish National Board of Education had high hopes for the project and saw that it would contribute to the national core curriculum reform that was on the horizon.

At the beginning I was overwhelmed by, and even anxious about, the lack of specific goals, and I found the question too general to get hold of an idea for development projects between students and teachers. I do not think like that anymore.

We continue to answer the question of how to create a great school for all. For example, two high schools, Kiteen lukio and Crowsnest Consolidated, studied local history during exchanges and even today are still co-operating. Two Finnish high schools teamed up with Edmonton’s McNally High School to organize different events and projects to raise funds to provide computers to a high school in Uganda. There were schools that wrote and recorded plays together.

One of our schools teamed up with Edmonton’s Jasper Place High School on a project aimed at increasing student participation and voice. This project has had a remarkable impact on how we are running our school, as students are now present and actively engaged at decision-making events like staff, project and team meetings. Their way of understanding the significance of our school was the basis of our value framework, and their voice has become significant to us.

Over the past five years, what used to be a treadmill of leading and managing unsustainable initiatives became a learning community for us all. We have learned valuable lessons by working together and paying attention, on both sides of the ocean. This is all fully documented in our report titled FINAL (https://asiakas.kotisivukone.com/files/seinajoenlukio.palvelee.fi/final-booklet_online_3.pdf).

High school students from Alberta and Finland discuss ideas for helping their schools become better learning environments.

While FINAL generated a lot of activity, its long-term implications were difficult to assess in the beginning since, like so many school initiatives, disruptions to our ways of doing things were hard to appreciate in the context of the broader systemwide changes happening both in Finland and Alberta. Looking back now, the outcomes are much easier to appreciate and place into the framework of national core curriculum reform and other educational goals. In so many ways FINAL avoided the risk of becoming merely an exercise in educational tourism. Instead, FINAL has informed our curriculum renewal here in Finland — a journey that both our systems will be undertaking in the years ahead.

Competence and Curriculum Reform

In 2014 I was fortunate enough to be invited by our ministry to take part in drafting and commenting on the national core curriculum for upper secondary education. The new core curricula were to carefully consider what changes were needed to provide up-to-date education and meet future demands, while other concerns related to making students feel at home at school and increasing their participation and well-being. Thinking about competencies rather than a focus on specific subjects became integral in the reform.

A new national core curriculum was available for grades 1 to 9 (basic education) at the end of 2014 and a year later for secondary education. Schools had to have their curricula plans ready by summer 2016 before starting their summer holidays. Starting from this new academic year, grades 1 to 7 will start with the new curriculum as well as Grade 10 in secondary education. The rest of the curriculum will come into effect in the years ahead.

A key question has emerged from this reform: what is the essential difference between competence and a conventional focus on discrete skills and knowledge?

In Finland, we prefer both a pragmatic and philosophical answer to this question shaped by the practical wisdom of our practicing teachers. When I consider my skills and competence related to international co-operation, knowing how to start, run and finish a project would be a skill. A competency would be an ability to successfully co-operate in a project in all circumstances, meaning I would need to be able to use appropriate language, understand people’s cultural backgrounds, demonstrate good social skills, be a team player, have good command of the topic, and the list goes on. In other words, competency is more context specific than discrete skills: it is an ability to successfully face the complex demands of a specific situation.

Developing a competency takes a long time and demands complex supports and inputs. One cannot learn it by studying one subject. Competence-based thinking places more stress on the interrelationships between school subjects, including knowledge building, and views school as a living entity or ecology.

The implications of these changes are significant, especially in terms of assessment. A shift to a competence focus renders conventional assessments like external standardized testing rather irrelevant and counterproductive. As well, the concern for what North Americans call “the basics” of literacy and numeracy can too easily become the driver for reform. The focus on competence includes literacy and numeracy across all domains of learning but, unfortunately, too often these can became the focus of practitioners and policymakers, which can mistakenly drive an obsession with international benchmarking such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

One of the challenges for Finnish education has been the fact that students do not feel at home while they’re at school. While we learned that Albertans framed this issue as student engagement, we shared our Alberta partner schools’ concerns that this term was being oversimplified through a focus on surveys and holding schools accountable for yet another new measure of success. For Finnish schools, we saw our students’ challenge as being much more complex. As the head of curriculum development at the Finnish National Board of Education, Irmeli Halinen, says in her blog, “Developing schools as learning communities, and emphasizing the joy of learning and a collaborative atmosphere, as well as promoting student autonomy in studying and in school life — these are some of our key aims in the reform. In order to meet the challenges of the future, there will be much focus on transversal (generic) competences and work across school subjects.”

Here Irmeli Halinen (2016) hits the soft spot of Finnish educational system and also signals the direction in which we should go. The new Finnish curriculum being implemented this fall aims at offering a new approach to learning and school culture with transversal competences at the centre.

One of the topics that we worked with in FINAL was student voice and how to make it active and heard at schools. Undeniably, there is a distinct analogy between what student voice meant in FINAL and what the notion of “student autonomy” means in Halinen’s blog. What we have done in FINAL implements competence-based thinking and increases student autonomy and participation. FINAL has emphasized the significance of student voice and how it is one of the key factors in creating a collaborative atmosphere and promoting student autonomy. For example, when we worked with McNally High School in Edmonton, we asked the students to take control of the process of raising money to provide computers for Ugandan schools while we, the teachers, assumed facilitator roles. This way we were able to give the students more opportunities to learn competencies and have ownership of their learning.

The Importance of Interdisciplinary Learning

Interdisciplinary learning has been discussed a lot in connection with curriculum reform, and co-operation between different school subjects has been encouraged. Breaking down the traditional subject-dominant thinking has caused disagreement and elicited criticism as it, among other things, challenges traditional learning and teaching routines. It also affects assessment and breaks down the traditional division of work at schools.

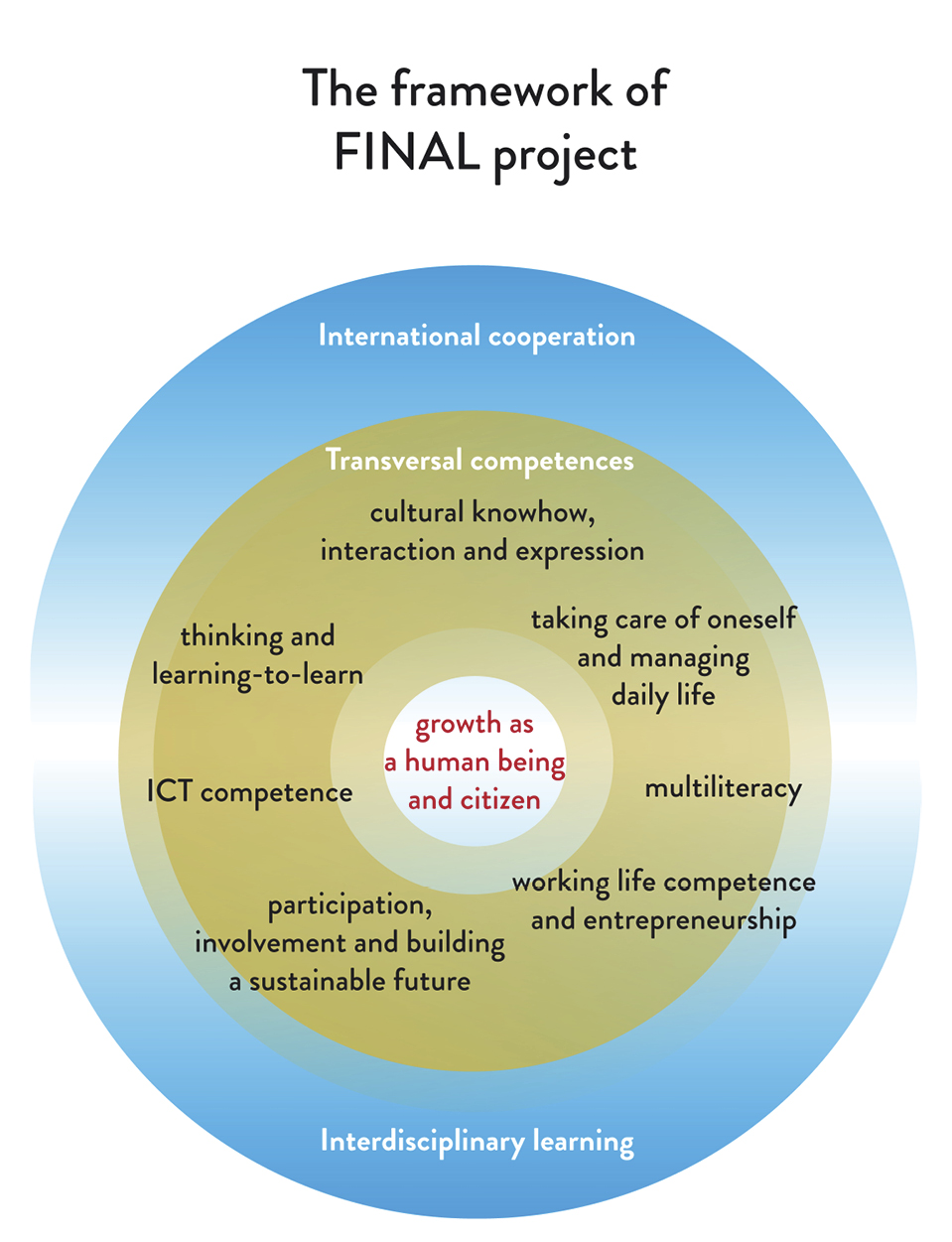

When it comes to interdisciplinary learning, there are no standardized or ready-made mechanisms for setting goals or assessing learning. Instead, these need to be negotiated, tailored and adjusted by the teacher, as a professional. In Finland we recognize that nobody can plan interdisciplinary learning/projects alone. This point is driven home by the complex interrelationships illustrated in the following figure.

I work in a school that has a long tradition of carrying out interdisciplinary learning and projects as part of regular school work, also with schools from abroad. I am proud to use the word tradition, as it implies that the (dirt) path we took many years ago has not proven to be too rough to ride. If I was asked to reflect on what has happened in our school, I would have mainly positive things to say. Reflecting on the transversal competencies, the seven areas of competence have been covered in most programs and projects.

When students work at interdisciplinary programs, their role becomes more active and autonomous partly due to the fact that they are extensively involved in planning, assessment, organization and execution. The students become agents of the process and not mere participants. An interdisciplinary approach will provide a more holistic view of a phenomenon than what a student could get by studying the phenomenon from the perspective of a single subject.

The change did not happen very quickly, at least not in our school. It has taken a number of years for students to start appreciating what opportunities they have, and it has also taken quite a long time for our teachers to start instinctively working together, exchanging ideas about what we could plan for next year.

What I have seen happen in classrooms with interdisciplinary learning or projects has often taken me by surprise. I have seen students and teachers planning their work and negotiating the timetables. I have seen students engaged in assessing their peers and also their own work. I have seen teachers being taught. I have seen different learning methods used. I have seen content faces and friendships emerge. I have seen arguing and the settling of arguments. But what actually matters the most is that I have been able to see people who are present there and then. I have seen a learning community. This is what I also witnessed at FINAL when students were working together.

International Cooperation in The Finnish Core Curriculum

International cooperation has been made prescriptive for basic education for the first time ever. That is remarkable in a sense because many still consider international cooperation an add-on and something that is not necessary at schools. Considering the transversal competences, it makes perfect sense that international cooperation is included. After all, it covers all the seven competence areas when it is carried out with careful planning and understood to be much more than exchanges, which are also valuable and provide positive long-term impacts on students, teachers and schools.

Paula Mattila, who is also counsellor of education at the Finnish National Board of Education, talks about different levels of internationalization, which could be freely translated as follows:

- Internationalization as attitudes, courage and understanding (individuals)

- Internationalization at home (schools)

- National and regional internationalization (regional and national projects)

- Mobilities/exchanges (cross-national projects) (http://www.polkka.info/kaytannot.html)

I find these levels useful for giving an idea of the depth of what international co-operation and internationalization can be and how differently they can be approached. Levels one and two can be dealt with by engaging a class in conversation whereas levels three and four require people from other places to work with.

When it comes to international co-operation, dissemination and impact should also be considered. Levels three and four can only be reached by a small number of students because travelling and meeting people is expensive and arranging online meetings cannot involve large groups. The key is how to share the message and the experience with the whole school. The impact of international co-operation can only be measured in one way — by examining what changes and innovations it has brought about.

The FINAL project works at all these four levels of international co-operation. The co-operation was discussed in schools and lesson material was prepared. As our final report describes, there were projects with online contacts between students and teachers. There was national and regional co-operation and projects, and there were exchanges.

What about the key word: impact?

This is what I see in our school. Currently we have four extensive interdisciplinary learning units and students have a more active role and a voice in developing their learning experiences. Teachers and students are more autonomous, innovative and ready to move out of their comfort zones. This is good for us but what counts more is the changes that are happening at the national level.

In spring 2016, the National Board of Education and the Ministry of Education launched a major national development project for high schools that will eventually involve 84 high schools in six different development networks. I was invited to co-ordinate a relatively extensive network covering western and middle Finland. Drawing on principles modelled by FINAL, the umbrella for the entire project is to enhance innovation and empower high schools to find their potential as agents of changing their own practices and school culture.

The project was launched in a seminar in late August. In my new role as co-ordinator of the western and central region of Finland, I look forward to working with colleagues to share our ideas, capabilities, hopes and fears as well as our dreams to find a direction for the development work ahead. True to some of the FINAL principles of innovation, we weren’t handed a project but we are to discover and devise it to suit our purposes. We have a long and interesting way ahead of us but also very significant and meaningful for what is going to happen in Finnish high schools.

I’m proud and privileged to have been part of FINAL because I’m now better equipped to co-ordinate the new project that employs the same principles and working methods as FINAL and also emphasizes student voice and participation at the centre.

References

Finnish National Board of Education. 2015. “What is going on in Finland? — Curriculum Reform 2016.” Blog posting by Irmeli Halinen. http://www.oph.fi/english/current_issues/101/0/what_is_going_on_in_finland_curriculum_reform_2016 (accessed August 29, 2016).

Järvilehto, Lauri. 2014. Hauskan oppimisen vallankumous. Jyvӓskylӓ: PS-Kustannus.

Mattila, P. 2010. Kansallinen kansainvälisyys ja muut koulujen

kansainvälisen toiminnan tasot. http://www.oph.fi/download/

126469_Kansainvalisyydentasotkouluissa082010.pdf (accessed August 29, 2016).

Ståhle. 2009. “Maailmassa tekemisen, tietämisen ja olemisen rakenteet ja haasteet ovat muuttuneet.” In Miksi ja miten suomalaiset opetussuunnitelmat muuttuvat, by Irmeli Halinen. http://www.oph.fi/download/152144_miksi_ja_miten_suomalaiset_opetussuunnitelmat_muuttuvat_08102013.pdf; http://www.oecd.org/pisa/35070367.pdf (accessed August 29, 2016).

Strauss, V. 2015. “No, Finland isn’t ditching traditional school subjects. Here’s what’s really happening.” Washington Post, March 26. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/03/26/no-finlands-schools-arent-giving-up-traditional-subjects-heres-what-the-reforms-will-really-do/ (accessed August 29, 2016).

Teijo Päkkilä works as a deputy head in Seinäjoki High School focusing on curriculum and development programmes. As well as his involvement in national curriculum reform he is an active writer and lecturer in Finland. His specialty areas are internationalization and foreign language education.

Students from the Canadian Rockies and Oulu, Finland take a break from curling for a photo op.